Mia up for the challenge

In my last blog post, just the other day six months ago, I spilled some virtual ink catching up on the summer and autumn of 2015 in a post that was like an iPhone 6, instantly obsolete and contributing little of value to your life.

A half a year later and I’m a full twelve months behind on updates so I’m going to make a year at the high-performance house building coalface vanish in a [not so] tight 3,000 words spread over a few posts along with a raft of photos [which is all people really want anyway]. I’ll try to be witty but what can you do when so much of it is just about insulation, and cross-bracing and high spec sealing tape?

So, casting back to 2015, after we got the metal roof on last October I took off to New Mexico for a Natural Building Colloquium, hanging out in the mountains west of the Trinity A-bomb blast site with people who eat plaster for breakfast and build entire houses from clay, straw and sweat.

Mum cutting vapour barrier in posh shoes

While I was away my amazing 70-something parents spent three days on their hands and knees on fractured drain rock putting down the impermeable sub-floor vapour barrier in our house and meticulously sealing it around every concrete peer with $80 a roll tape. The barrier is twenty times less permeable than the building code requires and is so tough you can drive construction equipment over it. I can’t overstate how vital this job is to the performance and comfort of our house, how much this sort of job isn’t my cup of tea and how brilliant my parents did with the sealing and detailing. They asked for a ‘substantial and important job’ and so they got it. They still have sore knees.

By the end of the year I’d laid down 6 inches / 15 cm of expanded polystyrene (EPS) foam insulation over the barrier providing thermal resistance of Imperial R24 / RSI 4.23 / U0.23. I have deep ambivalence about using EPS ‘expanded foam’ – the stuff ‘disposable’ [as in last for 1,000 years] coffee cups in the bottom of landfill sites used to be made of. It’s substantially less bad than the rigid pink or blue extruded polystyrene (XPS) foam, which uses much more potent greenhouse gasses during manufacture. But at the end of the day all foam insulation is basically petroleum-based plastic soaked in fire retardant, as are so many commercial building products. This stuff pains me and buying a truck load of the stuff pained me even more.

The sub-floor EPS cross to bear.

I contemplated using Rockboard, a firm mineral wool board from Roxul, but it is hard to find and unaffordable at nearly six times the price of EPS, which also had the advantage of being manufactured locally near Vancouver. A better natural option I learned about too late in the game was hempcrete or ‘hemp lime’ [lime mixed with the inner part of hemp plants], which would have been worth considering for the sub-floor and the walls. It may well appear in the next project and I like it so much that I commissioned this book.

On the upside, despite the billions of foamy balls which plugged and burned out our borrowed vacuum, and the child sacrifice screeching sound when I cut it that had Karen in hysterics, substantial EPS sub-floor insulation over an impermeable barrier results in a bone-dry floor with a very slow rate of heat loss to the earth. This is the absolute inverse of the half-subterranean, damp, stone floor-over-bare earth deep freeze that Mia lived in as a baby in Crystal Palace, South London. When we moved from that flat, the carpet under the bed was covered in mould and we had to bin the almost new mattress. Of course that place was a virtual Atacama Desert compared to our Streatham flat. It’s so often these cold, damp blanket recollections of my UK housing experiences that drive my quest for very warm and very dry in our house.

Bizarrely, like Hyde, after I was done the sub-floor insulation I sort of wished I’d used even more EPS and laid down 12 inches / 30 cm of EPS to double the floor insulation, as if I lived in Flin Flon rather than the [imaginary] Canadian Riviera. When is enough, enough?

On top of the EPS, which has an impressive compression rating of about 2300 lbs/sf / 11,300 kg/m2, we framed the internal ground floor walls of the double wall system making 16-inch / 40 cm thick exterior walls downstairs and 12-inch / 30 cm thick walls upstairs. During this time, my sister dropped in for a few days from Calgary and for an early 50th birthday present I showed her how to use the mitre saw without losing fingers. She chopped studs while I nailed and we managed to frame out the double walls of both the upstairs gable ends over a weekend.

This whole internal double wall framing business involved nearly six weeks of building custom top plates and air baffles and extensive air sealing detailing using roll after roll of [really, really, really expensive] Siga Wigluv sealing tape. The temptation to get lazy was always and ever present and the only antidote was lunch, coffee and judicious eyedroppers of my not-quite-buried childhood perfectionism.

As the foolish Europeans who arrived to colonized this place fewer than two centuries ago never knew, the BC coast is historically a brick-shitting deadly seismic zone. To mitigate [some of] the risk posed by a megathrust earthquake, which builds with every passing hour that the Juan de Fuca plate sticks to the North America plate in the Cascadia subduction zone, my engineer specified heaps and heaps of cross-bracing. So, I spent weeks and weeks cutting and nailing 2X4 ‘X’s into the double walls to a prescribed pattern until the entire house was thoroughly cross-braced.

There are a numerous seismic features in the house. The concrete foundation pinned into bedrock and large, frequently spaced anchor bolts and heavy steel post tie-downs should keep the house from doing the table cloth and dinner plates routine in a big shaker and sliding off the foundation. Hurricane ties between the roof and the walls, galvanized strapping between the gables and the rim joists and many, many dozens of foot long engineered GRK structural screws and heavy bolts should keep the layers of the house from flying apart. Lastly, the cross-bracing should in theory keep the whole thing from buckling. At least that’s what the calcs say, though the upward seismic limit isn’t known. With massive earthquakes it’s all about distance, depth and duration and unknown, unknowns.

About the same time we added the cross-bracing, in went the sub-floor plumbing for the toilet, bath, sinks and water delivery lines. Then we wheel-barrowed in and compacted 11 tonnes of road base [gravel, sand and clay] as a solid base for the eventual earthen floor. Much more on this later when you get to watch a video of Mia laying floor.

For now, here’s some more pics of insulation and cross-bracing and sealing tape.

See, now that contributed value to your life.

Fiddling with the vapour barrier

Pleased as punch

Completion photo

Pier detailing

Water line and power line penetrations

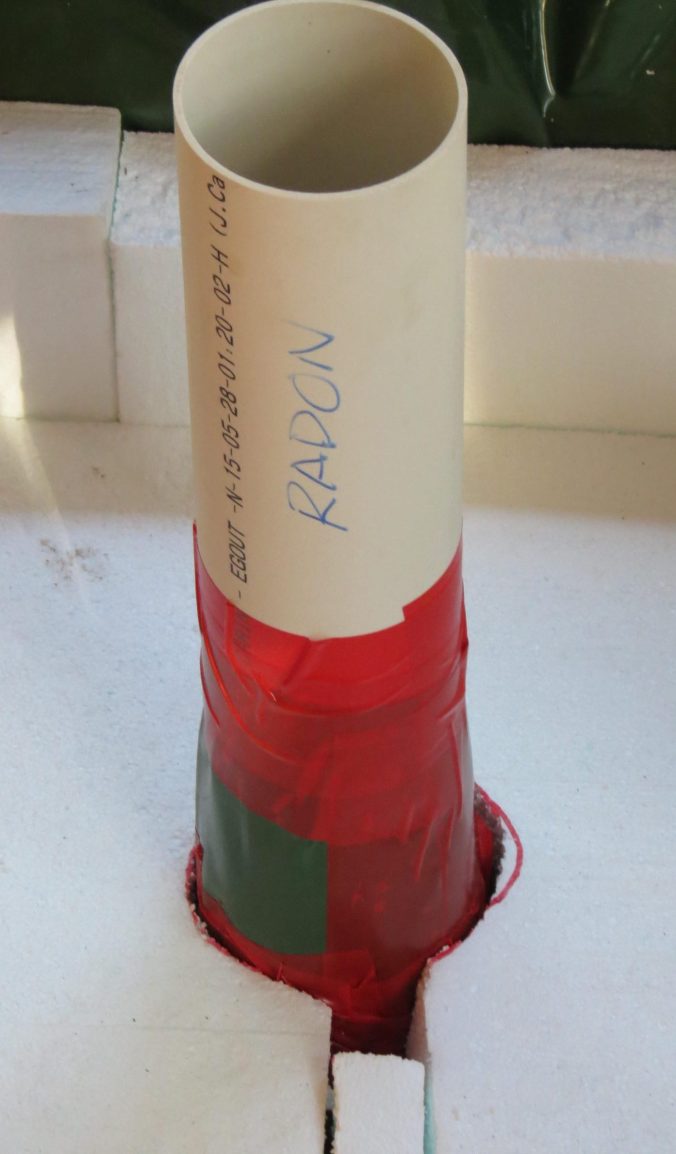

My ‘just in case’ radon gas mitigation pipe

Sub-floor waterlines for the loo and the toilet flange

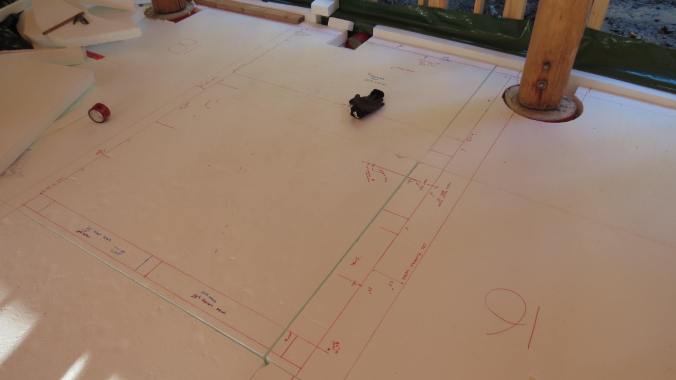

Laying out the downstairs loo walls

More subfloor plumbing

Sealing the sub-floor vapour barrier to the exterior sill plate

And nailing it for life

Laying out the floor plates for internal walls

X bracing at a window

And more

And more

Shear wall X bracing

and more

Custom double wall top plates and Siga tape air sealing

Gable end double wall

More air sealing

Collar ties I added to create the plane of the upstairs ceiling, and the future chimney location

Dormer air sealing baffles

Upstairs double wall with X bracing on the outside

Pat chopping studs like a high schooler

One sip and she’s blurry

Karen moving road base

And more

And much, much more

Mia spreading the road base

Rob on the plate compactor

And look what happened in the garden. The elderberry tree was blooming

And some early flowers